I wasn't planning to go to Poland. But about eight weeks ago the opportunity came up to attend a conference as part of Reading Malopolska, exploring Cities of Literature networks. Krakow, Poland's 'second city', after capital Warswaw, is bidding for UNESCO City of Literature status. Melbourne was awarded this title about three years ago.

So last week I spent three days in Krakow, in the company of City of Literature representatives. I went wearing my Melbourne Writers Festival hat, to see about developing contacts with other cities and people as part of this group. You can see a nice video summary here.

Now there are six Cities of Literature: Edinburgh, Melbourne, Dublin, Iowa, Reykjavik and Norwich. Almost all English language cities, I'm sure you noted. But here comes a new wave of applicants from cities including Krakow, Naples, Heidelberg, Tartu and Prague among them.

What is most interesting about the Cities of Literature is the different responses that each makes to the brief. In Melbourne thus far it has been mostly "top-down": the establishment of the Wheeler Centre being the flagship. But in Edinburgh, Dublin, Iowa and elsewhere, leaders have taken a vigorous grass-roots approach to the promotion of reading and to spreading an awareness of each city's literary heritage.

Which brings us back to Krakow. Because if the city can boast anything, (though boasting isn't the style of this quiet, historic city), it's literary backstory. Krakow is home to two - count 'em - Nobel laureates, Czeslaw Milosz and Wislawa Szymborska, and a heritage stretching back a millennium at least. The challenge for the city's cultural workers is figure out how to move forward without dispatching this extraordinary heritage. A country whose own political heritage has been so disrupted might well be anxious how 'modernisers' try to re-define Polish literature to the world. The conference organisers were acutely mindful of such anxieties, or the potential for such. But culture that exists only in a glass case is either dead or about to be so, and the opportunities for UNESCO recognition are an opportunity to revive the heritage, and take it outside the country. It might also be a platform for new writers to engage new audiences, at home and abroad and validate new endeavours.

Krakow is a city of extraordinary cultural riches, not just literary. For one, there is a da Vinci painting Lady With an Ermine that you can see, relatively uncrowded, in a medieval castle. For two, there is the biggest medieval market square in Europe (beneath which you can wander in the 13th century foundations). And for three, there is the 14th century gothic altarpiece by Veit Stoss. A truly extraordinary work of religious art, with a backdrop of towering stained glass.

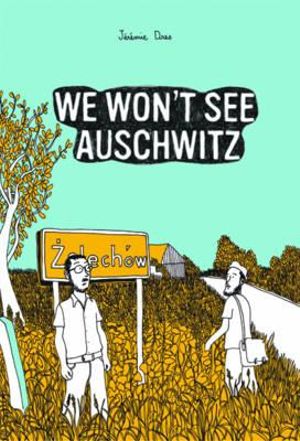

Krakow is also the departure point for anyone wanting to go to Auschwitz, about 40 kilometres from the city. While I have absolutely no objection to anyone wanting to go the site of the concentration camp, I have no desire myself. I feel there are plenty of ways for me to understand and examine the realities and legacies of the genocide, but physically going there is not something I want to do. So it was quite some coincidence to discover a few days later in a bookshop (Foyles, in London), the graphic novel We Won't See Auschwitz by Paris-based Jeremie Dres. The book is a straightforward account of a trip taken by the writer and his brother to Poland in search their family's past. The illustration style appears simple, though it's nuanced and economical. I like the documentary approach. It's not without a few lighter moments, and the journey is presented without complication or need for artifice.

Dres is relatively un-conflicted about not visiting Auschwitz, (spoiler alert: the title is not ironic, there is no surprise twist), since he discovers amid the suspicion of lingering anti-semitism, a new wave of endeavours to bring Jewish heritage and culture back to Poland. there are people working on humanitarian, cultural and legal fronts to re-establish a new space for Polish Jews. Rather than remain fixated in one way of remembering the past, Dres draws us towards a view that there is more going on in Poland than a simple reading would lead us to believe.