The latest issue of Viewpoint: on books for young adults, includes my review of two recent graphic novels. Neither book fits easily into the received notion of 'graphic novel', which is probably why I like them so much. Thanks to Pam Macintyre and the team for publishing the reviews.

A Taste of Chlorine

Bastien Vivès (Jonathan Cape, hbk)

and

Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie A tale of love and fallout

Lauren Redniss (It Books/HarperCollins) hbk

A Taste of Chlorine (Goute de Chlore) by Bastien Vivès, the young Parisian writer/illustrator won the Revelation Award for best first book at Angouleme in 2009, Europe’s biggest comics festival. Simply put, A Taste of Chlorine is the story of a teenage boy ordered by his doctor to swim regularly to repair a damaged spine. At the pool, he comes into contact with a young woman who offers him advice on swimming technique and companionship. As their tentative relationship develops, companionship leans towards attraction.

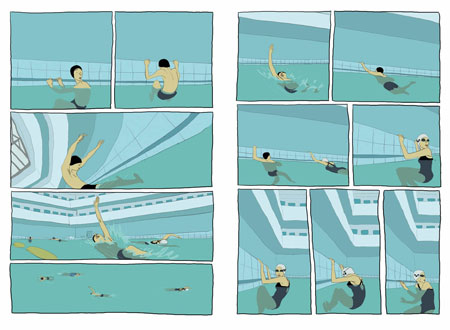

Most of the action takes place at the pool and in the water. Bastien Vives delights in depicting the body’s curves and lines in all its various positions, shapes and poses. What, after all, is swimming, if not contorting the body into striking shapes? All those aquatic blues and greens lend the book a certain cool mood, punctuated by the black ribbon of the lap lanes. The minimalism of the colour and location allows the viewer to attend more closely to the emotional exchanges, since below the surface however and emotional drama of subtly and force plays out. In this regard A Taste of Chlorine is a remarkable debut, a book where the artist shows us what he can do within the tight confines of setting. Vives exploits perspective and point of view with some authority. It is also a book that is long on visuals and lighter on text, but that doesn’t mean that viewers will simply skim the book (The act of swimming is not a language-based activity, so why not remove all but necessary language from the pages?) The drawing sometimes appears simple, even at times rudimentary, but this is somehow in keeping with the story’s unaffected emotional tone.

One reads this book as one watches a film, where the dynamics of space and gesture are all important. Vives also neatly exploits the use of the ‘frame’ or panel as a way of isolating his characters. There are points where the panel behaves like the lanes of a pool, bringing the swimmers closer yet exquisitely resisting the shared moment so desired by the young man. A Taste of Chlorine does not give up its secrets easily. Perhaps it doesn’t need saying that the book will not be to everyone’s favour. But this quiet, deftly told drama challenges some received ideas of the graphic novel. The ending is enigmatic, open, and will have keen viewers returning again and again, to tease out the elusive relationship at the heart of the story. A Taste of Chlorine is also an example of the innovation that the French graphic novel, la bande dessinee, is capable of achieving, as artists and writers explore the creative potential of the form.

Radioactive works differently. It’s a book relatively long on text and strictly speaking, is not really a graphic novel. Well, insofar as it does not use the panel structure to tell its story, and avoids speech balloons. But the life of Marie Curie, the remarkable scientist, is passionately communicated through sophisticated picture-making and bold page design. Again, the drawing style has a slightly ungainly, improvised manner, which is belied by the confident use of colour to shape mood and emotional response in the reader. After all, an account of a scientist whose major work was more a hundred years ago, may not immediately hold great interest for the reader today. That this world is remote gives way at the first glance of the endpapers. (Doubt stops at the border.)

Pages often employ a full-bleed (colour to the edge of the page) that reinforces a slightly ethereal, otherworldly quality. The absence of the authorial frame supports the otherworldly dimension of radioactive materials that were the working tools of Marie Curie’s life. The extent to which she and husband Pierre exposed themselves to these deadly substances soon becomes plain and provokes an immediate anxiety in the heart of the reader. We know this won’t end well. Still, one reads the book with a sense of excitement too. Marie Curie was not a woman to sit aloof from life in her laboratory: she also loved, suffered and survived scandal. Interleaved with the Curie’s life and their discovery of radioactivity, are stories of the implications of their research. Here Redniss uses, for example, eyewitness accounts of Three Mile Island, Hiroshima, and points the way to which nuclear power might fuel space travel. So science is not kept in a museum, put on a pedestal and admired. Author/artist Lauren Redniss shows us some of the consequences of the use of uranium and raises questions that remain urgent.

The pages are beautiful, some Rothko-like in their floating planes of colour. Others exploit reworked photographs, playing with the idea of a scrapbook, an album of memories. This is a book that throws off any shackles of the worthy aspects of non-fiction. I think in the end, Redniss and the reader are suspended between two points. On the one hand we marvel at what Marie Curie achieved, the sacrifices she made - and what science has unlocked. Radioactive is science with a human heart and wonderful, memorable and moving book. Try and catch it.

For a taste of Radioactive, visit the New York Public Library, where Lauren Redniss researched the book.

For a taste of Radioactive, visit the New York Public Library, where Lauren Redniss researched the book.

Lastly, both of these books are published by smaller imprints of major publishers. Let’s hear it for the promotion of experimentation and risk in an age of caution and anxiety.

2 comments:

Beautiful review, Mike. I do love a 'clean lines' graphic - so many feel rushed, hurried, chaotic - a work that gives you space to breathe is a good thing.

Amazing-looking stuff!

Post a Comment